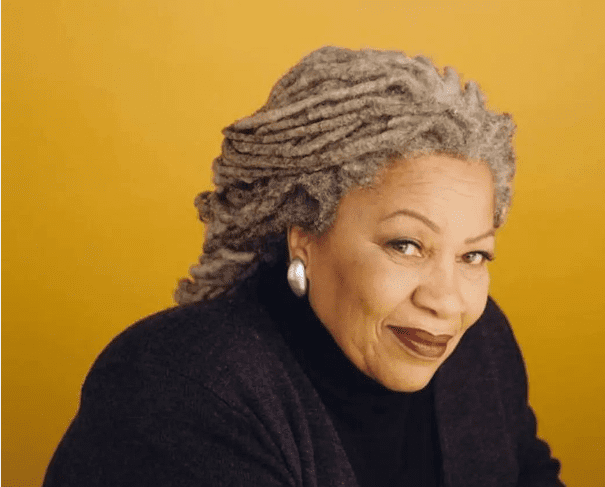

In some reviews of Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, the upbringing of the hero, Neva, has been interpreted as either heroic and poetic positive eulogizing, or as comic banter and irony. Aiming at these two absolutism criticisms, this paper points out that Song of Solomon is not a text without cracks, but two different purses and different styles of singing under the smooth surface of the novel symbiosis. This split of the text not only removes the rigid stance on the relationship between the sexes, self/others, history/reality embodied in the song, but also overcomes any simplistic and absolute judgment on the baby’s growth journey.

Toni Morrison’s novel Song of Solomon presents a strange reality filled with African American folklore, song and spirit. The story takes the hero’s journey back to his grandfather’s land as a clue, showing the hero’s inner journey of discovering and reinventing himself. There seems to be a solid core of bildungsroman in Morrison’s labyrinths, and Morrison jumps into the mold of the literary Canon with her root-finding stories in disguise. This interpretation places “Song of Solomon” in a familiar critical context, where it relates to classical mythology, heroic epics, traditional coming-of-age novels, adventure romances, and self-seeking modernist classics. Nai Wa, the hero, is also interpreted as a classical individual hero or a modernistic protagonist in pursuit of a complete self and sound reason. The novel ends with the baby flying “as bright as the North Star” over the opposite hill, a highly publicized imagery rare in Morrison’s novels that has critics eagerly hailing the baby as a cultural hero who has rescued black history and tradition from the willful oblivion of the white mainstream narrative. [1] In this interpretation, Song of Solomon seems to be easily claimed by the Western tradition of individual heroism, presenting nothing more than a “localized” Odyssey for black people. However, in fact, Morrison’s text has never been such a type of understanding and determination, such a large heroic aura only makes the baby’s image more suspicious. The novel ends with Milkboy’s journey to her roots, despite the bright “North Star,” still tinged with loss and regret, as Hagar is dead and the barriers between Pilat [2], Ruth and Macon remain unchanged. As Morrison noted in an interview, the archetype of the “flying man” in black culture speaks of tragedy and grandeur, but also of “the consequences and regrets of such heroic feats” [3]. So critics have tried to turn the cultural hero interpretation on its head in different ways, reading the joke and irony in between the lines. In their opinion, Morrison does not so much perfunctory a traditional male bildung-of-age novel in the context of black culture, as she looks on and parodies this literary tradition from the perspective of the other in western white culture. And Milkman’s cash-strapped, coping journey is more fitting for a clown megalomaniac than a man who sets the Solomon family straight. [4] Thus, the ambiguity of the novel itself and the two conflicting interpretations that derive from it make Milkboy’s journey of self-creation and self-destruction worth rereading and reassessing.

Morrison’s novels tend to focus on black women, and when discussing why she chose an unknowing young man as the main character in Song of Solomon, Morrison pointed out that she wanted to write a novel about how a man from scratch learns from the women around him and matures under their influence. Throughout the novel, the baby is surrounded by some extraordinary women. His journey of self-growth and root-finding actually began and ended with a woman. From Michigan to Danville to Shalimar, from Pilat to Circe to Susan, it was women who inspired and guided him. The most important of these guides was his aunt Pilate, who was often seen as the baby’s pilot. It was from her that the baby heard the Song of Solomon throughout. But while the story between the baby and the women hints at the classic plot of a hero exploring the unknown under the guidance of a spiritual guide, there is no sing-along between teachers and students. It might be said that the baby had literally taken possession of Pilat’s song, but had deliberately turned away from her singing; Or he uses the knowledge he gets from women to build a system of his own. For the baby, the process of questioning and possessing the Song of Solomon is a process of self-construction, the most masculine ritual of his bar mitzvah. A well-defined male self was a goal he grew up obsessed with. His male self was born and nurtured in the return of deciphering his lost father’s name and recovering his father’s shadow. The Solomons’ primogenship gave him a complete, clear, unambiguous identity, and helped him emerge from nameless invisibility and aphasia to gain a place in the well-documented currents of history. In contrast to milkman’s searching male self-construction, Pilat is more like what feminist writer and cultural theorist Gloria Anzuodyua called Mestiza consciousness. Unlike the standardised male consciousness in white Western societies, it is not rigid, normative, or either/or, but “flexible and flexible”. It does not rely purely on reason to reach a precise and absolute goal (a consciousness echoed to some extent by Milkman’s journey to Solomon), but on divergent “multidirectional thinking”. [5] The singing Pilat is no longer a self in opposition to the other, but a subject drifting between different consciences, a medium through which the collective “I” can make confessions. It is in the transboundary wandering that Pilat Bridges the dismembered personal, family and racial memory, and embodies the existence of self in the flow. Milkboy’s songs, therefore, have a different purpose from Pilat’s. Milkboy is not so much a student of women as a misreader of women and female singing, trying to extract words from their fluid and loose texts and attach them to his own increasingly consolidated structure. Thus, the Song of Solomon, which serves as the novel’s central metaphor, is not an impenetrable monolith, but a schism and play between two different kinds of singing. What makes Morrison unique is that she neither sticks to tradition and falls into the mold of adventure romances, bildungeons and root-searching stories, nor does she deliberately parody subversion and completely defect from the classic genre. Her singing of “Song of Solomon” activates two interwoven texts under a smooth fictional surface. In the novel, the growing story of the hero occupying the main line and the female’s loose or absent existence attached to his growing experience constitute two different levels of text and two different kinds of singing. The existence of this split prevents the novel from simply succumbing to any one absolutist interpretation (the two opposing critiques outlined above, cultural hero and comic parody), but instead brings the ambiguity and richness common to black women’s writing. Critical differences about the baby and his coming-of-age story are thus resolved in the novel’s hidden two-voice singing. Any single, absolutely exclusive interpretation is bound to fail to fully parse the complex texture of the Song of Solomon.

Singing is a vital survival posture for both Pilat and the growing baby. Different motivations and ways of singing have contributed to their different interpretations of the meaning of Song of Solomon. Through the cracks of the text, we see two different temperaments thinking about personal identity, racial history, black cultural tradition and reality.